*

The two competing versions of Shakespeare's Much Ado About Nothing that opened this week are reminiscent of the war of the Macbeths. In 1849 two productions of the Scottish play opened in New York. One starred William Charles Macready, the greatest British actor of his generation. The other was Edwin Forrest, the first real American star actor. The two hated each other, their rivalry fueled not only by their very different approaches to the classical roles — Hamlet, King Lear, Macbeth, and the contentious issue of who was a better actor — but also by the explosive Anglo-American relations of the time, which pitted the mainly working class Irish-American supporters of Forrest against the anglophile upper classes who preferred the Englishman.

On the evening of May 10, 1849, both actors were due to play Macbeth at theatres only a few blocks apart — Macready at the Astor Place Theatre, Forrest at the Broadway. The mayor, fearing that feeling among the actors' rival supporters was running too high for the city police's ability to cope, called out the militia. By the time the performances began at 7:30, there were 10,000 angry people in the streets. What started as the ill-mannered throwing of rotten eggs, vegetables and other missiles outside the theatres soon degenerated into a full-scale riot; by the time the smoke cleared some 30 people were dead and hundreds were injured. The roof of the Astor Place Theatre collapsed on the heads of the audience and some of the rioters tried to set fire to both theatres. Although it would be inaccurate to say that the only cause of the Astor Place Riot was the rivalry between competing views of Shakespeare, it is indisputable that Macready and Forrest were the emblems of the battle then raging between the British and American worldviews.

|

||

| David Tennant in Much Ado About Nothing. |

||

| photo by Johan Persson |

Meanwhile, in a parallel universe, over at Shakespeare's Globe, they were already planning their own, more traditional production of the same play. This time the putative lovers are Charles Edwards, a West End and National Theatre actor with the timing of a well-adjusted clock, and Eve Best, Olivier Award–winning classical actor best known in the United States for her very funny turn as the English doctor on "Nurse Jackie." For my money, the Globe version allows Shakespeare to speak more clearly and, although the couple at Wyndham's is starrier, Eve Best and Charles Edwards have a goofy sweetness laced with a gravity that will win hearts and minds all summer long. Elsewhere on the Rialto are other wonders. At the miraculous National Theatre, where they turn water into wine on a regular basis, a reworking by playwright Richard Bean of Goldoni's 1746 comedy A Servant of Two Masters has been blissfully returned to us as One Man, Two Guvnors. It contains a treasurable performance from James Corden as the dopey but lovable amanuensis of both a diminutive gangster who turns out to be a girl (Jemima Rooper) and an adorable upper-class twit (Oliver Chris), supported by the kind of dream cast the National now routinely fields. It is part English end of the pier, part French farce, part Italian commedia dell'arte. Heaven.

Also at the National is Chekhov's The Cherry Orchard, with Zoe Wanamaker as Madame Ranyevskaya, which makes up in intellectual heft what it lacks in emotional warmth. And although Madame and her family are as maddening as ever in their refusal to sell the orchard to pay their debts, at least we have someone to root for in the person of their upstart neighbor, Lopakhin, played impeccably and with total honesty by Conleth Hill.

|

||

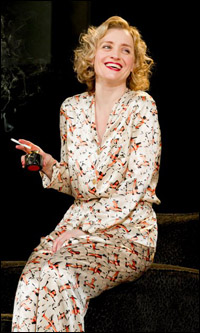

| Anne Marie Duff in Cause Célèbre. |

||

| photo by Alastair Muir |

In conclusion, two American revivals: At the Almeida, Edward Albee's A Delicate Balance is a pitch-perfect production by James Macdonald with the best cast in London — Penelope Wilton, Tim Piggott-Smith, Imelda Staunton — and an infallible ear for the class and regional implications of this coruscating, New England-set family drama. And at the National Theatre there is Rocket to the Moon, a rare look at a 1938 play by Clifford Odets originally written for the Group Theatre. At its center. a married dentist, of all things, yearns to break free from his constricted life, even if it's only to have an affair with his secretary.

(Ruth Leon is a London and New York City arts writer and critic whose work has been seen in Playbill magazine and other publications.)

*

Check out more of Playbill.com's international coverage, including London correspondent Mark Shenton's daily news reporting.