*

Behind Shakespeare's Curtain

Before there was Shakespeare's Globe, there was Shakespeare's Curtain. Well, not his actually, not the way the Globe was Shakespeare's because he was a major shareholder, but the newly discovered Curtain, built in Shoreditch, just outside what were the city limits in 1577, is where Romeo and Juliet and Henry V had their premieres. It is in Henry V that Shakespeare refers to the Curtain as "this wooden O." The Curtain and its neighbor, the Theatre, were necessarily outside the city limits because of legal limitations on places of entertainment in London which, of course, is why the Globe was built on the South Bank of the Thames in Southwark. All, however, were walking or ferry distance from the center of the city.

Now, with the discovery by builders of an exterior wall which is indubitably part of the Curtain, the developers have decided to build an outdoor 250-seat auditorium with a glass-enclosed museum to preserve its original features. It is in London's least lovely borough, Hackney, although having a world-class heritage site there might help, and the plan to build a mixed residential and commercial development around the Curtain, to be named The Stage, is already raising hackles among Shoreditch's less theatrical residents.

The Curtain is a new-build by comparison with the 1,500-year old amphitheatre that was found in 1988 under the building site for the Guildhall Art Gallery. It was built by the Romans when they occupied Britain from 43 A.D. until 410 A.D. In its time it was a multi-use space, used for gladiatorial contests, wild animal fights, public executions, and, of course, theatre. This month the 5,000-seat auditorium, the only one of its kind in London, will stage a play for the first time in 1,500 years, Euripides' Medea. The gallery isn't expecting an audience of 5,000, though, but a more select few of about 100 to see the play as Euripides intended — in an amphitheatre, with an all-male cast, and, of course, a Greek chorus.

|

At the time of writing, the jury is struggling to decide on the winner of the sixth annual Sheridan Morley Prize for Theatre Biography. My Playbill colleague Mark Shenton is on the jury this year, along with actor — and 2011 shortlisted author — Isla Blair and theatre director Braham Murray. As non-voting chair of the jury, I'm delighted with this year's shortlist because it encompasses all that's best about theatre writing.

The prize is given for the best biography, autobiography, or theatre diary published in English during the preceding calendar year, and this shortlist is, I think, the best ever. However can the jury choose between the brilliant and hilarious memoir by Rupert Everett, "Vanishing Years"; Sue Prideaux's widely researched and meticulous "Strindberg, A Life"; and Simon Callow's "Charles Dickens and the Great Theatre of the World"? (Read the Playbill story about which author won the prize here.)

And that's not all. I loved actor Michael Pennington's one-man show where he simply stood onstage in an old sweater and talked about Shakespeare. Now he's put it between hard covers as "Sweet William," and it's a joy to read. Arthur Laurents, the difficult but great Broadway producer and director died in 2011, but not before completing "The Rest of the Story," the second part of his autobiography in which he is wonderfully nasty about everybody. That is on the shortlist alongside Kate Bassett's portrait of Jonathan Miller, "In Two Minds." What a list. Next month, I'll report in on the award ceremony at London's Garrick Club, the home of 18th-century actor David Garrick.

|

||

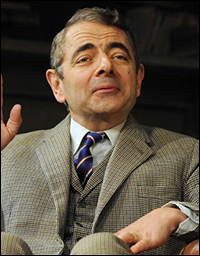

| Rowan Atkinson in Quartermaine's Terms. |

||

| Photo by Alastair Muir |

Max Stafford Clark was the original director of Timberlake Wertenbaker's breakout play, Our Country's Good, in 1988. Now, in 2013, he returns to her wonderful drama about the early settlers of Australia, the convicts and the military officers who drew the short straw by being sent 8,000 miles from home to keep them under control. One young officer suggests that discipline will be easier if the prisoners are trained to put on a play, and from the meager store of plays in the officer's library he chooses Farquhar's The Recruiting Officer. Preposterous, you might think, but it actually happened. And it worked. Nearly all the characters are based on real people, and Stafford-Clark's tiny cast at the new St. James Theatre, doubling and tripling roles as both officers and convicts, make sense out of the nonsensical and turn into a company of actors from a rabble. So good to see this play again. I think directors should return to their early triumphs much more often. The only thing missing here is that, in its earlier incarnation, Our Country's Good ran alongside a crosscast production of The Recruiting Officer. I wish they'd done that again. (It ends at the St. James March 23.)

You either love Simon Gray or you don't. Gray was my late husband's favorite contemporary playwright and I can't help but admire the craft that goes into every line, even if I don't much care for his characters. The title character in Quartermaine's Terms, now in a new production by Richard Eyre at Wyndhams, is a case in point. As played perfectly by the erstwhile Mr. Bean, Rowan Atkinson, this pathetic milquetoast isn't anyone I want to spend ten minutes with, despite feeling desperately sorry for his loneliness and sadness, but here I am, stuck in a theatre with him for more than two hours. The rest of the cast is terrific, too, but I don't like any of their characters much either. Must be me.

David Hare's The Judas Kiss tackles Oscar Wilde's last day of freedom before he is hauled off by the police to be tried for homosexuality. Now here's a character I really do like and on whose behalf I'd be more than willing to stand by the barricades if anyone had asked me — and if I'd be born at the time. Rupert Everett, bulked up by a fat suit (I hope), finds all the wit and sensitivity in Wilde, and in Hare as well. This is a really good play, transferred from Hampstead to the West End.

I've been having a lot of fun at the other end of my, admittedly limited, spectrum. Instead of seeing a play as I usually do, at the end of the rehearsal life, when it's ready to be seen by an audience, I was invited by Stephen Unwin, director of Noel Coward's The Vortex, to early rehearsals at the Rose as the actors began to explore the Coward's early drama of sex, drugs, and, no, not rock 'n' roll, but definitely incest. Music does, in fact, play a major role but that's another story. Watching the seriousness of the actors and director as they exercised their considerable talents to discern the meaning behind each line and gesture was a revelation. It wouldn't be appropriate for me to review this production, obviously, but do watch out for a young actor called David Dawson who plays the leading role of Nicky. He's a star. Or, at least, he will be. (Ruth Leon is a London and New York City arts writer and critic whose work has been seen in Playbill magazine and other publications.)

Check out Playbill.com's London listings. Seek out more of Playbill.com's international coverage, including London correspondent Mark Shenton's daily news reporting from the U.K.